Bring on the bloodied exchange of Viking swords!

Tom Morton on weddings and funerals in the UK’s northernmost archipelago

Here in the northernmost, weddings are easy. Funerals are hard.

It seems so obvious, and before my first wedding here in Shetland as an official, legal, properly certificated celebrant, I’d have disagreed.

There was so much to get wrong in a marriage, so many ‘what ifs?’.

Had the couple been to the Registrar, filled in all the forms, paid their fees and obtained the schedule they and the witnesses would have to sign at the ceremony?

Would I, and they, put their names in the correct place? Would whoever they handed this precious proof of wedlock to remember to take it to the Registrar once the celebrations were over, and not lose it in a Champagne/Prosecco/Cava/Cremant frenzy?

What of fountain pens and indelible ink, both required by the Registrar General of Scotland who had, in consternation watched past ballpoint signatures gradually fade away in the archives? And insisted on gold nibs and Quink? What of left-handed couples with no previous experience of traditional stylography? What of potential leaks onto expensive dresses?

In the end, it doesn’t matter, because love, joy and the prospect of sparkling wine conquer all.

And even if my much-loved Lamy and the brand-new Waterman both DID leak at my last two weddings, only fingers were smudged, and linen tablecloths. And desperate handkerchiefs. Not a single wedding dress was harmed. Much.

Also, I talked the couples concerned out of what is now called handfasting, or they both sensibly talked themselves out of it. This fashionable combination of bondage and neopaganism (not that I have anything much against neopaganism, except the pneumonia factor of all that compulsory naked dancing) as you may know, involves ribbons or tartan scarves and symbolic knotting of the couple’s hands together.

Most of my fellow Celebrate People people will perform this, but frankly, as someone who’s never been able to tie anything but a granny knot (banned from the Scouts at an early age) I won’t. You’ll have to get knotted elsewhere.

Other celebrants are available.

Modern tartan handfasting’s roots lie in the Norse or Old English ceremony whereby a couple would signify their intent to be together by simply taking each other’s right hand. The word ‘handfesta’ in Old Norse means ‘to strike a bargain by holding hands’ and holding hands seems to me a perfectly reasonable expression of affection, even for Scots. Oh, and not that Celtic at all, not really. Anyway, Chris and Astryd held each other’s hands, slipped rings on each other’s finger, made their vows, and that was pretty much that.

It’s easy, in all the flowers and sometimes showbizzy glamour of a wedding ceremony, to forget that what is happening is contractual and legal. Which is why, when I’m approached by a couple who’d like me to marry them, I tend to ask why they want to have a (let’s face it, quite expensive) Celebrate People celebrant rather than the simple, much cheaper formality of a Registrar doing the business. Sure, location can be important, writing your own vows, expressing love in a public way. But hey, Susan and I were married in Rutherglen Registry Office, me hungover as hell, poured out of the Burgh Bar, her eight and a half months pregnant, uncertain to the last over who might or might not attend. And so far still going after nearly 40 years.

It’s all about love and intention, and I suppose what Celebrate people celebrants do, each in their own inimitable way, is provide a vehicle for a couple to express that.

But as I say, weddings are easy, because everyone wants happiness to be the order of the day: love, affection, joy. A little spilt ink isn’t going to spoil things. Hopefully.

Funerals on the other hand…

Full disclosure - I’ve officiated at well over 100 funerals, and two (so far; more booked) weddings. I don’t know, maybe prospective seekers of legal nuptials here in Shetland are concerned I’ll get mixed up between the two ceremonies.

Most of the funerals I’ve conducted have been in the isles. That has meant, for the most part, burial, as there’s no crematorium here. The nearest is in Aberdeen and while some families will opt for a memorial service with or without ashes present, the vast majority of Shetlanders want to be buried in their local graveyard.

And what yards these are; from the astonishing cemetery of Norwick, on Unst, the most northerly Shetland isle, to the equally beautiful southern outpost of Levenwick, third island down. Lund, though, on Unst, with its ancient and secret monastic fish carving, hidden from the viking marauders, still makes me feel like the merest speck in an awesome history.

Emotions at a funeral are deep, painful, agonising. Old fears and wounds resurface.

Everything you say has to be correct or eternal offence can be caused. It’s a painstaking business, preparing and writing and rewriting, then speaking to a hurt and grieving audience.

Trying to find bits of humour in telling a life story, yes,but not so you diminish the tremendous loss you’re marking.

But there is something utterly elemental about walking with that coffin to the grave, lowering it in, saying the words of committal and then crucially, leaving it behind. Walking with the family and friends away, back to life, to go on with the process of living and breathing and having our being . And often heading to the hall for the requisite purvey, storytelling, a few drinks. Community.

From death to burial in Shetland is usually, aside from necessary legalities such as post mortems, quick. Less than a week, mostly, which means that preparing a service, visiting the bereaved family, making sure what’s said is correct and meaningful, is intense work. And with a funeral in somewhere like Yell or Unst taking up a whole day, much of it spent travelling by hearse and ferry, it means the work of a celebrant takes three intense, detailed and emotionally draining days.

I’m in an unusual position with Celebrate People as I don’t feel able to charge for taking a funeral. As a local councillor I see it as part of my duty to the community that has given so much to me and my family. If folk want to make a donation to the local foodbank, then they can..

Oh, and I can be as religious or secular as the family want. I’ve found myself asked to recite part of the Roman Catholic mass for the dead, read exceedingly robust John Cooper Clarke poems; I’ve played music by the Red Army Choir, said the Lord’s Prayer countless times, and sung a variety of hymns.

As my colleague Libby McArthur has already said in these pages: there is no need to chuck the Baby Jesus out with the bathwater. Humanist? With a small ‘h’.

Meanwhile, there’s the prospect of a proper Old Norse wedding. None of that wimpy and complex handfasting but the customary exchange of weaponry. There was a discharge of firearms after a recent marriage but that was celebratory and in the air.

Viking weddings usually involved the enforcing of peace between two warring families, and the exchange of broadswords or axes, often bloodied. So far we’re going for swords, and no blood. Not until the reception, anyway.

Funeral to follow? Let’s hope not!

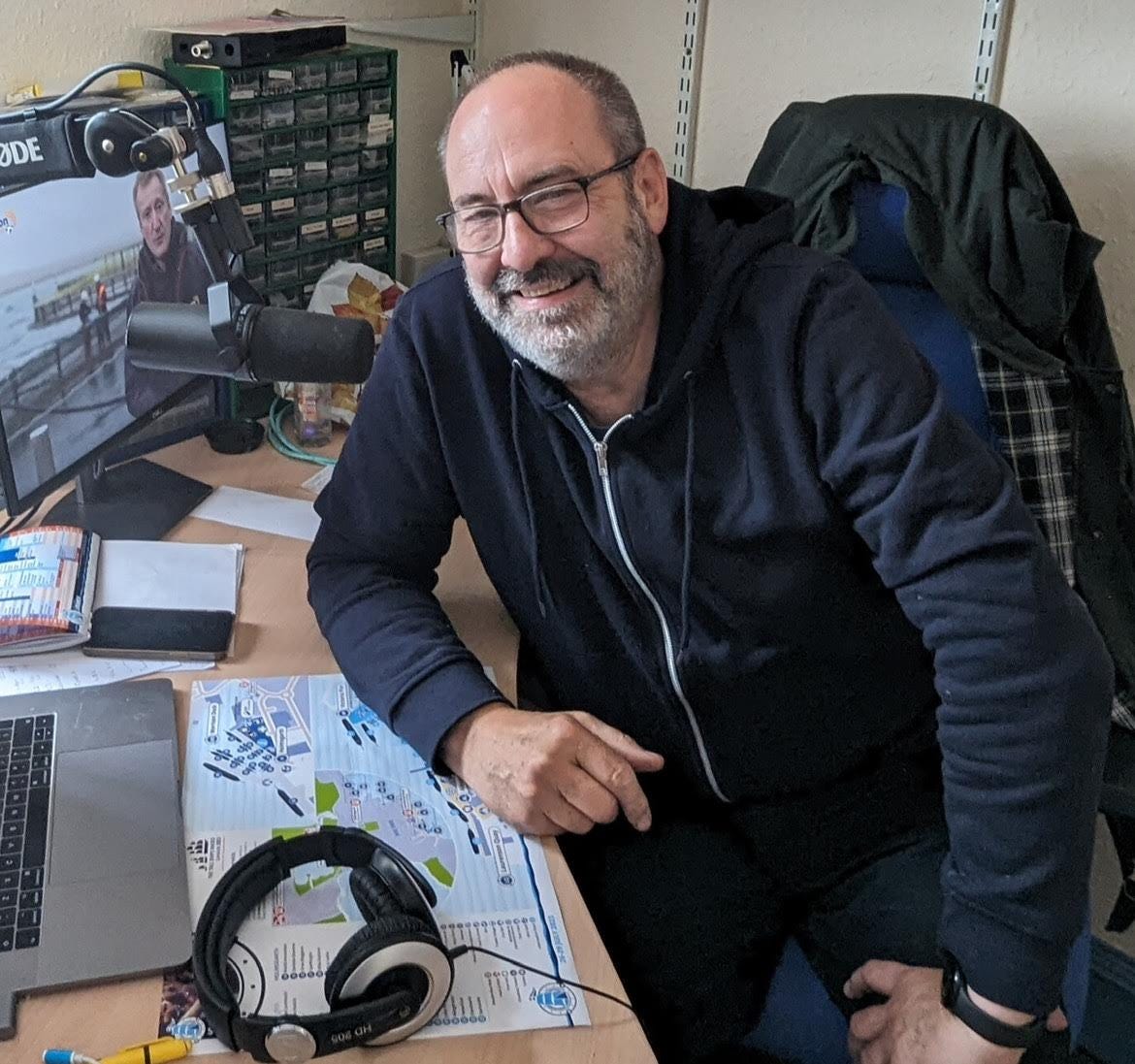

Tom Morton is a celebrant, Shetland Islands councillor, writer and broadcaster based

mostly in the Shetland islands but sometimes in his native Ayrshire.

He is the author of It Tolls For Thee: Celebrating and Reclaiming the End of Life (Watkins Books).

Find him online at tommorton.live

“love, joy and the prospect of sparkling wine conquer all”Indeed they do, but anyone who has the opportunity to be married by you is going to have a fabulous ceremony as well!